Dear future undergraduate researcher

Dear future undergraduate researcher,

I’m writing this letter to you because I want to convey to you the lessons I took away from my own undergraduate research experiences in computer science.

This is a long letter because I wanted to include examples and context to the lessons. I’ve written about 6 different problems and approaches (labelled A-F) I faced during my undergraduate experiences. These are:

- Problem A: How to find a good project? → Approach A: By finding a good supervisor.

- Problem B: How to find time to do research? → Approach B: By making time to do research.

- Problem C: How to track/make progress in research? → Approach C: By having a research doc.

- Problem D: How to become more efficient at doing research? → Approach D: By learning about other people’s tools.

- Problem E: How to have better meetings? → Approach E: By preparing for meetings.

- Problem F: How to find confidence/motivation to keep doing research? → Approach F: By building and relying on your support network.

A thought: my motivations for writing this letter. One dream I have as a graduate student is to be a good graduate student mentor. I think an important part to being a good mentor for undergraduates is having the ability to understand undergraduate students. I recently finished my undergraduate studies and before time dilutes my memory of my undergraduate research experiences, I decided to write a blog post about what I learned from those experiences. Diving into research (an entirely different career than what I considered doing) and computer science (an entirely different major than what I considered doing) was scary for me because of the uncertainty. Will I be good at research? Will my project turn into anything? What will the future hold in store for me? I write this letter to alleviate some of that fear I had as an undergraduate.

Problem A: Finding a good project.

When I first came into college, I didn’t really know what my interests were, let alone how to use my interests to find a research project that fit me. Sure, I had a vague notion of what I liked (chemistry) and disliked (physics), but my interests lacked specificity and experience. How should I find my footing in research if I don’t really know what I like doing or if I don’t have experience in a field?

Approach A: By finding a good supervisor.

I think a good supervisor is much more valuable than finding a good project because they will teach you the skills you need to become a better researcher. They will help you flounder around less.

What makes for a good supervisor? A good supervisor is a person:

- Who gives you guidance to turn your vague interests into concrete (dis)interests.

- Whom you like working with.

Example 1. During freshman year, I thought I liked doing chemistry so I tried out a research project in a chemistry lab. I had a really awesome mentor that taught me all the wetlab basics himself: He taught me how to pipette properly, helped me reproduce experiments from prior research papers, and indulged in all the questions I had. I ended up realizing that I didn’t like doing wet lab work. However, I’d like to strongly emphasize that I’m really grateful for my mentor to have given me the actual experience to realize this early on during my undergraduate. This enabled me to try other majors, such as computer science (CS), where I’m now doing my PhD in.

Example 2. During my sophomore year, I became interested in computer science and started doing research on digital wearables. I was really excited about the project, but a few weeks into the experience, I started to enjoy it less because I didn’t like working with my supervisor. We didn’t talk very often. I didn’t feel like they cared about whether I was learning anything useful because they would often brush off my questions and ideas for the project. Plus, other undergraduates and I frequently had to set up demos for lab visitors and replicate one of the graduate student’s old project because it turned into a sellable product. This experience actually gave me an incredibly negative impression of research and I decided to not do research for 6 months afterwards.

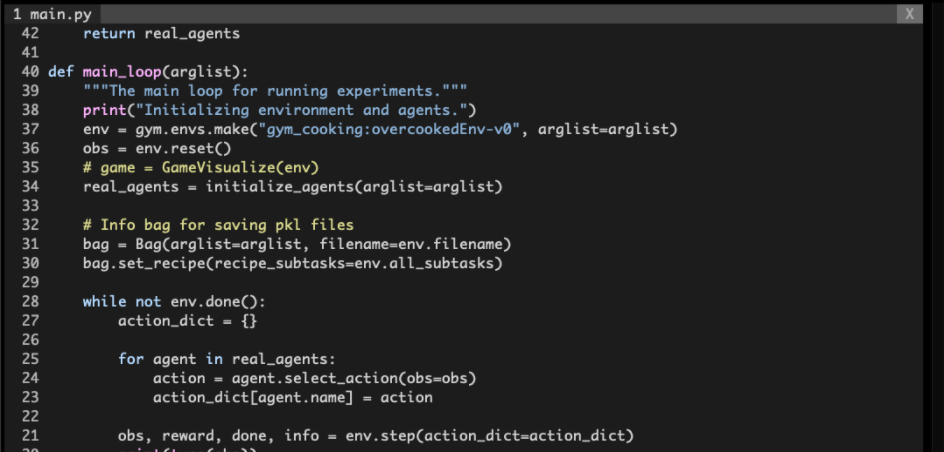

Example 3. At the near end of my sophomore year, I listened to a seminar talk about a robotics project. I found the talk really interesting and went up to the graduate student to ask whether I could research with him. He took me on even though I had no robotics experience and less than a month of programming experience. I had a lot of research freedom to learn about robotics, and he made the time to sit down, give me direction/resources, point me to people to talk to, etc. I had a really positive experience working with this graduate student, and I became really interested in doing research again — this time in multiagent systems.

So, how do you find a good supervisor? I don’t have a brilliant, safety-proof answer since I crossed paths with my graduate students by a combination of chance and biased search. Nevertheless, here are some useful “rules of thumbs” I’ve gathered from friends and from my own personal experiences.

- Have a few initial conversations with the graduate student. Get a sense of who they are as a mentor. What’s their personality like? What’s their mentoring style like? What are their research interests? Do their interests align with yours? If there are red flags (e.g. the supervisor doesn’t seem kind to undergraduates), listen to your gut.

- Have a conversation with previous undergraduates the graduate student has mentored or is currently mentoring. Do those undergraduates enjoy working with the graduate student? Do they feel supported? Weigh the pros and cons of working with the graduate student — I think the graduate student would be understanding since both your time and their time are valuable, and so you should find a reasonable match.

- Try working with the graduate student for a few months and see how it goes. This assumes the research opportunity allows for this kind of flexibility.

Reflection on A. An important note I want to stick here is not to confuse “a good supervisor” with “making fast progress in research”. Starting to do research usually is a slow process and there’s a lot of unpredictable things in research. That’s why I think it’s important to at least find a supervisor that has your best interests in mind.

Your undergraduate studies should be a time for you to explore your interests. You deserve to find both a project and supervisor right for you, and sometimes that takes a bit of trial and error—at least it did for me. Don’t be discouraged if that process takes long. Even if you don’t find something for you right away, I believe you’ve gained even more valuable insight into what you don’t like doing and what you do hope to find. Use that as your heuristic on your search for an even better project/supervisor.

Problem B: Finding time to do research.

A problem I faced once I found a project+supervisor I liked was finding the time to do research outside of classes and clubs. I would start off the week wanting to accomplish a set of research tasks, but as each day of the week passes, I would get carried away with the flurry of class assignments, readings, exams…and before I knew it, the semester was over and I didn’t accomplish much in my research project.

Approach B: By making time to do research.

The advice sounds simple, but as an undergraduate, I found it hard to follow because there were always interesting classes to take/clubs to be a part of. Even if you’re adding “easy” classes or clubs that take “very little time”, these are still things that take time away from research. No amount of time management can help you create time that’s simply not there.

After spending the first two years of college wandering around/trying out different majors, I decided to take research in CS very seriously my junior year. I talked with my supervisor that I wanted to go through an entire project lifecycle — from coming up with the research idea to publishing the project at a conference. I knew that in order to actually follow through with this goal, I need to make time to do research. So, I intentionally:

- Took low-commitment classes. I took 3 technical classes and 2 nontechnical classes.

- Did not do any extracurricular activities/clubs. I did make time for running, swimming and hanging out with friends though.

- Did research first, then homework assignments. For me, I found that I could spend an infinite amount of time on homework assignments and end up having very little time for research. This is why I tended to do research right after classes, and homework assignments whenever I finished my research tasks.

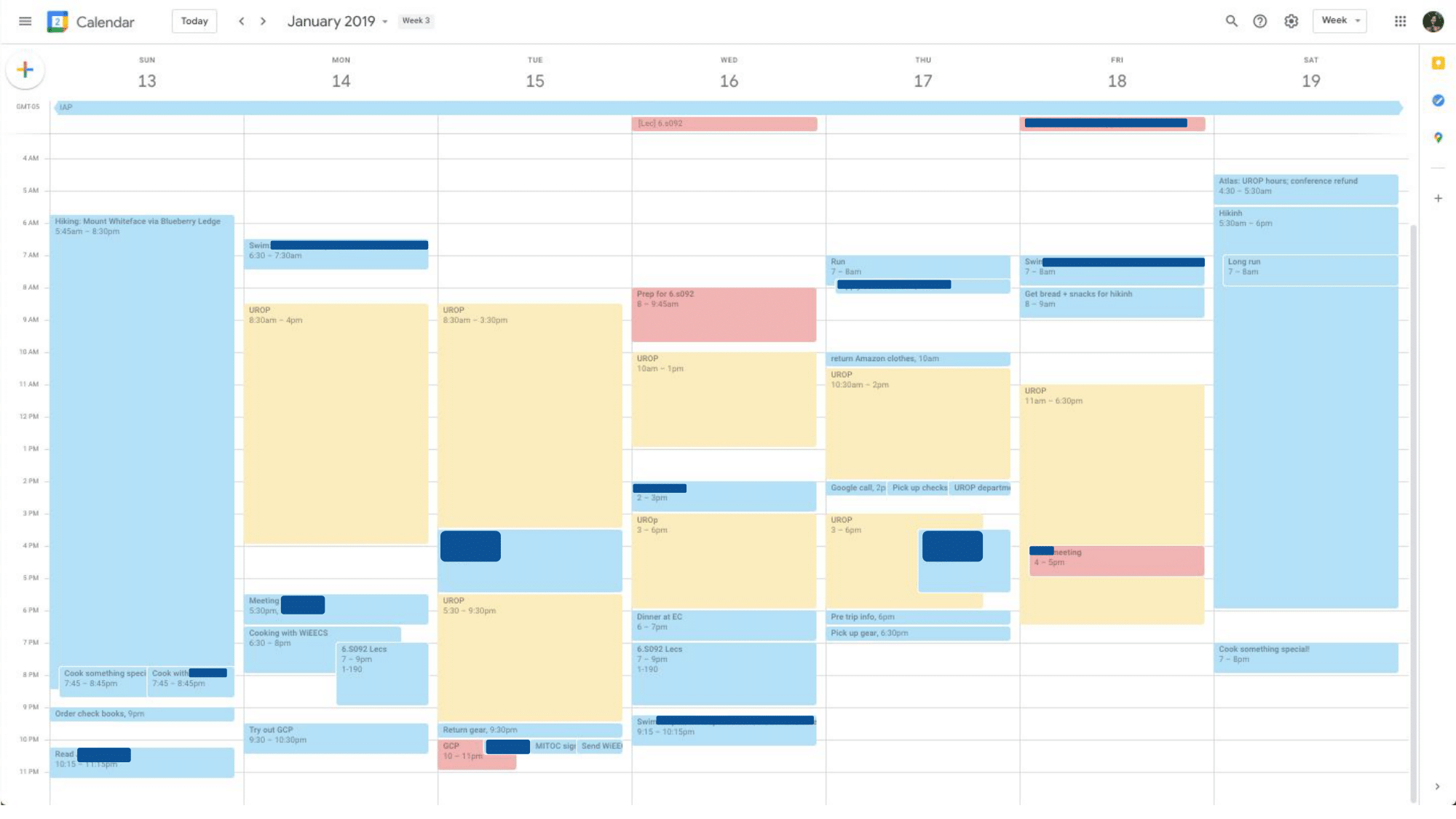

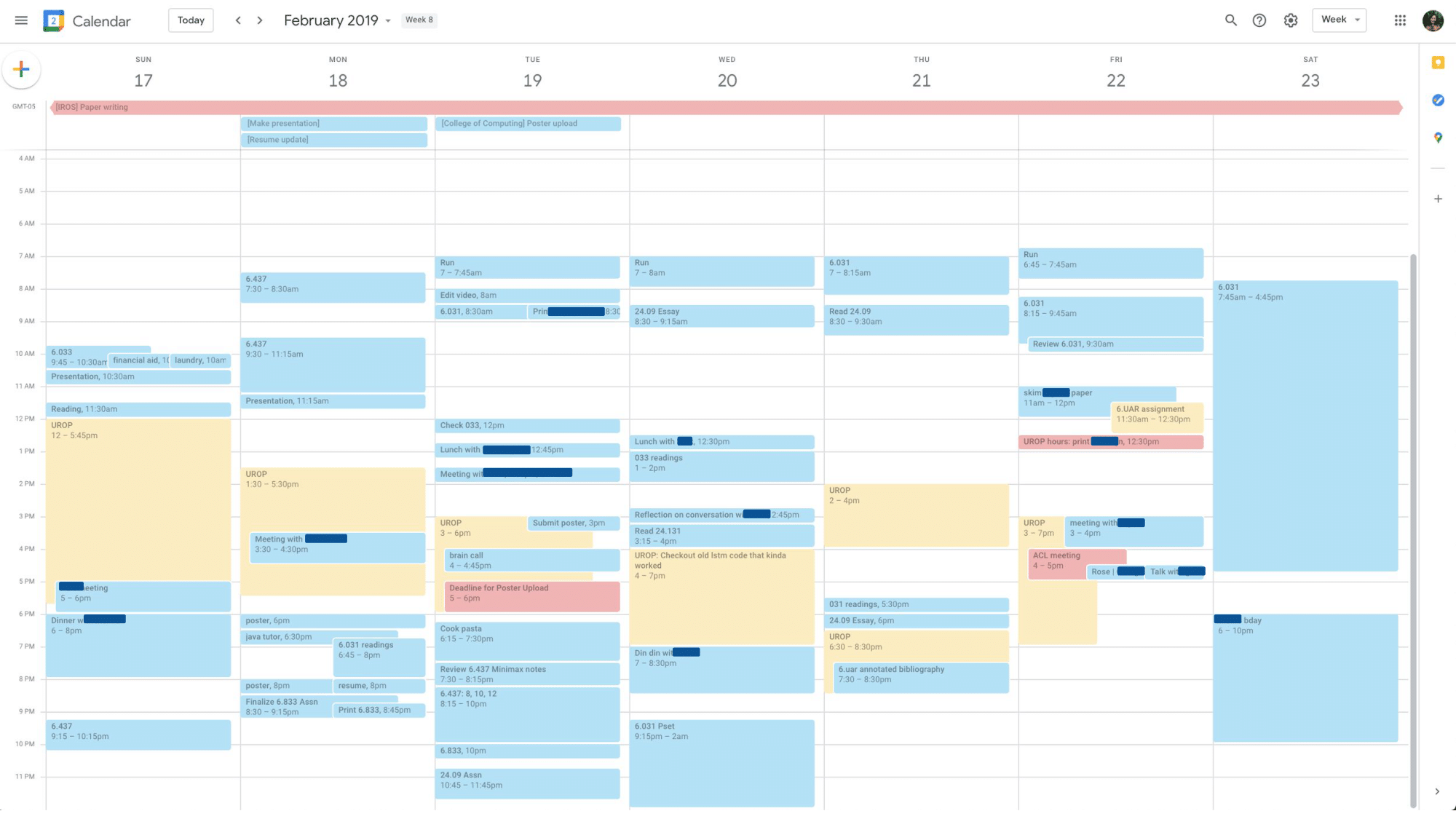

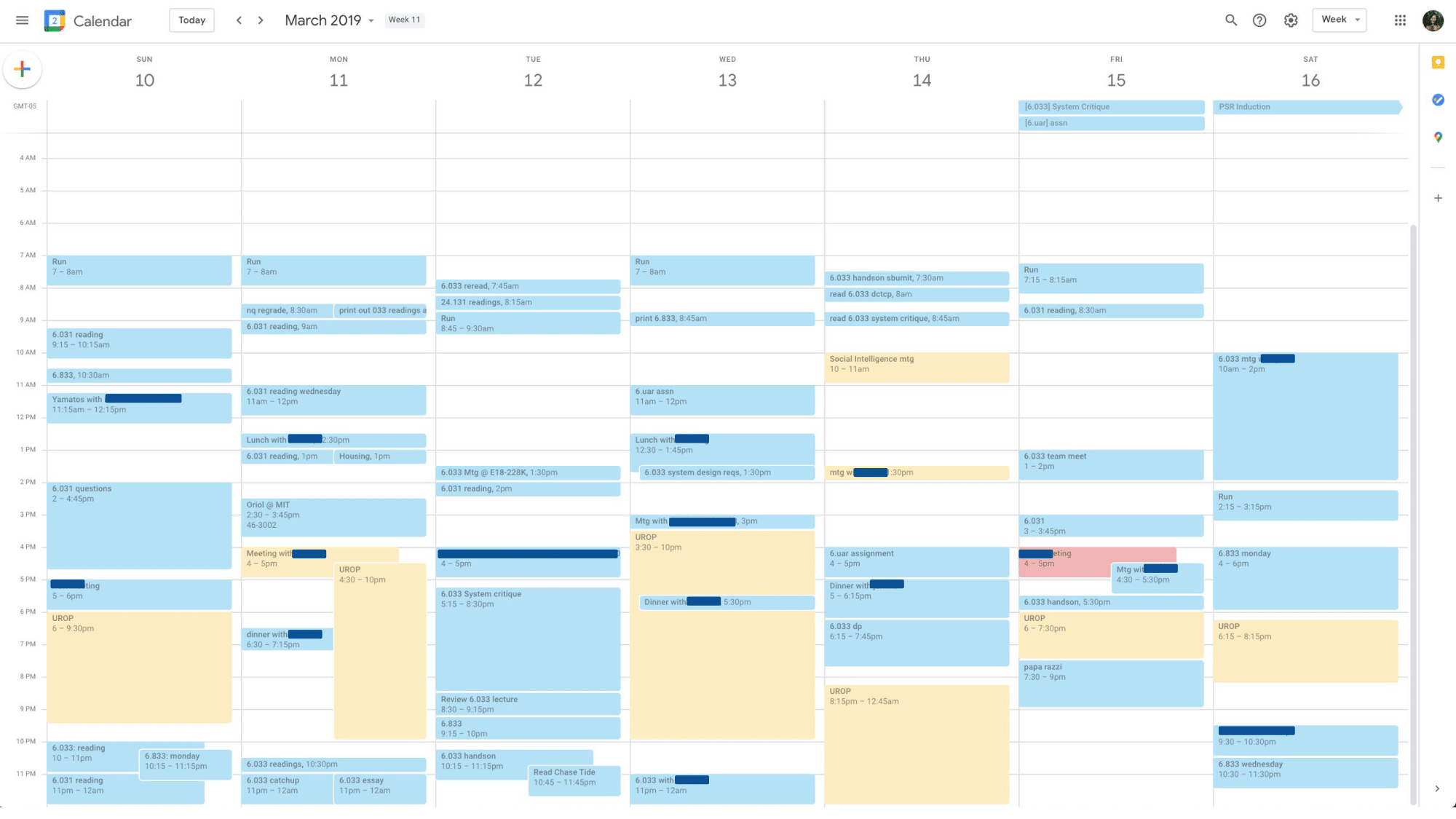

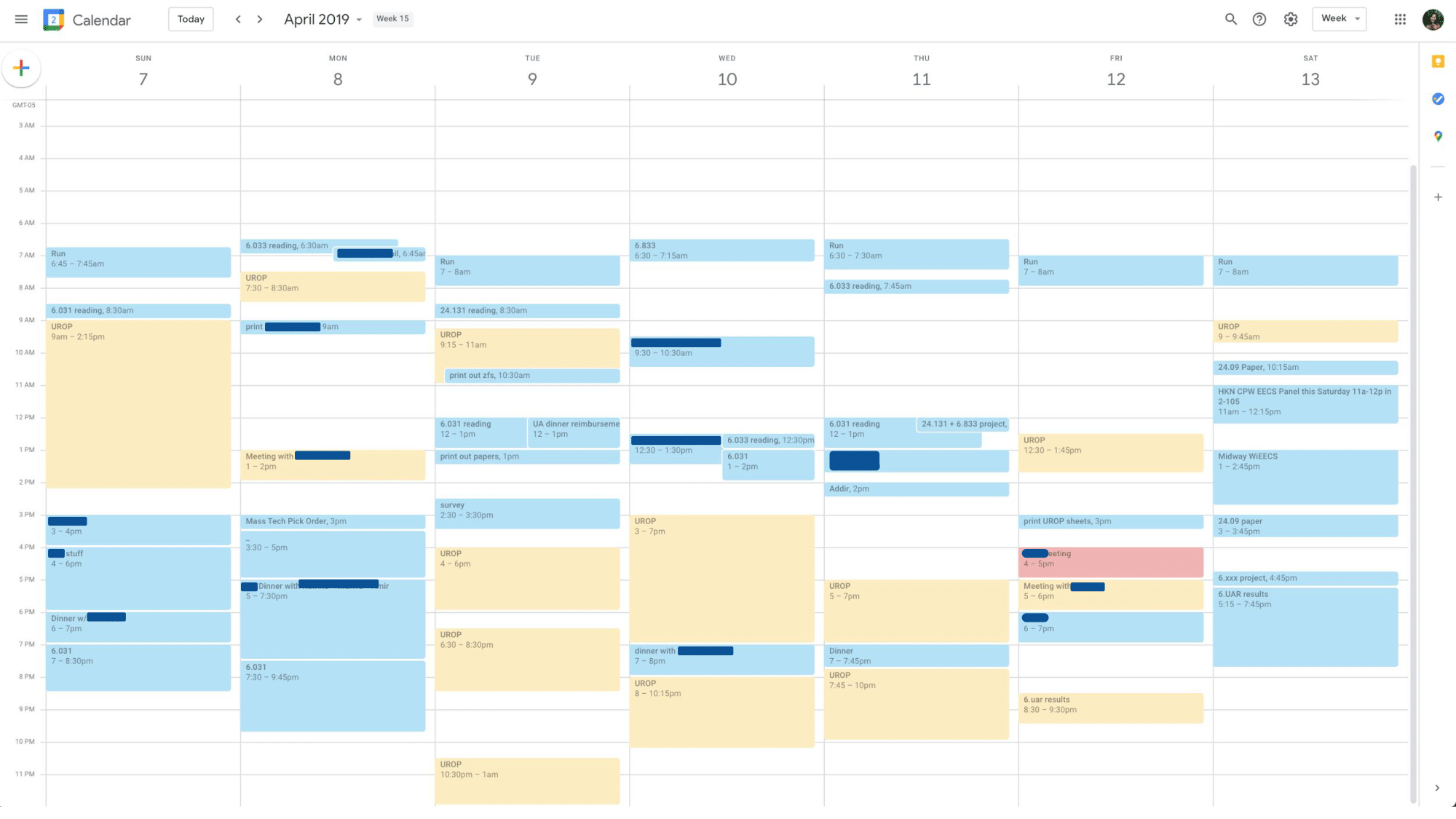

As a result, I was able to spend about 15-30 hours per week doing research. Here are some screenshots of my junior year calendar. Yellow are the times I spent doing research. There are empty spaces in the calendar where presumably I was in class/not doing research.

Reflection on B.

A completely unplanned for result from committing time to doing research is that I got to build a lot of research momentum which became incredibly useful for the projects I did during my senior year. Concretely, what did this momentum lead to?

- I built depth in my research area (multiagent systems). Because I was constantly exposing myself to the small-big problems in multiagent systems, I accrued a long list of interests/directions I wanted to explore within this research area.

- I became familiar with the research process. I found this familiarity to be extremely helpful my senior year when I started a new project in a new lab and when I led my own project during my 4-month internship at Google Brain Robotics.

- I built the confidence to do research. Research was no longer a completely mysterious activity/career. I felt a bit more steady on my feet doing another research project!

I’d highly recommend spending a summer doing research to build up this momentum. Since I was pretty serious about research during my junior year, I decided to stay on campus to do research the summer of my junior year.

As an addendum to how I created more time to do research, here’s a list of random optimizations I found to work well for me.

- I planned experiments ahead of time. I planned most of my experiments the day before, so running them usually meant pressing enter on a command in my terminal. I started running experiments during class. This way, after class, I could see the results of the experiments and continue from there.

- I wrote essay assignments during class. I took two nontechnical classes that assigned essays on a biweekly basis and I enjoyed writing these essays during the respective class lectures. I found the lecture content to nicely complement the essay assignments anyway. Typically, I spent 30 minutes sketching out an essay outline so that I could spend the 1-hour lectures writing the essay. I’m not sure whether this is the most responsible/appropriate piece of advice to give, but I found this to work well for me. This also meant spending 1-hour less on homework assignments outside of classes and 1-hour more on research

- I invested my free time into my health. For me, investing in my health is not a distraction from research. It is a direct contribution to my research productivity because it makes me happier. I found two things to be important for my health. One was running in the morning (~7am). The other was having enough social time with friends. Every day, I always got lunch and/or dinner with a friend (or with my lab), or worked with friends in an empty room somewhere on campus. I also generally took Friday nights off.

Problem C: Tracking/making research progress.

I believe one of the most challenging parts in research is overcoming the feeling that you’re not making progress and continuously engaging with your work.

Approach C: By having a research doc.

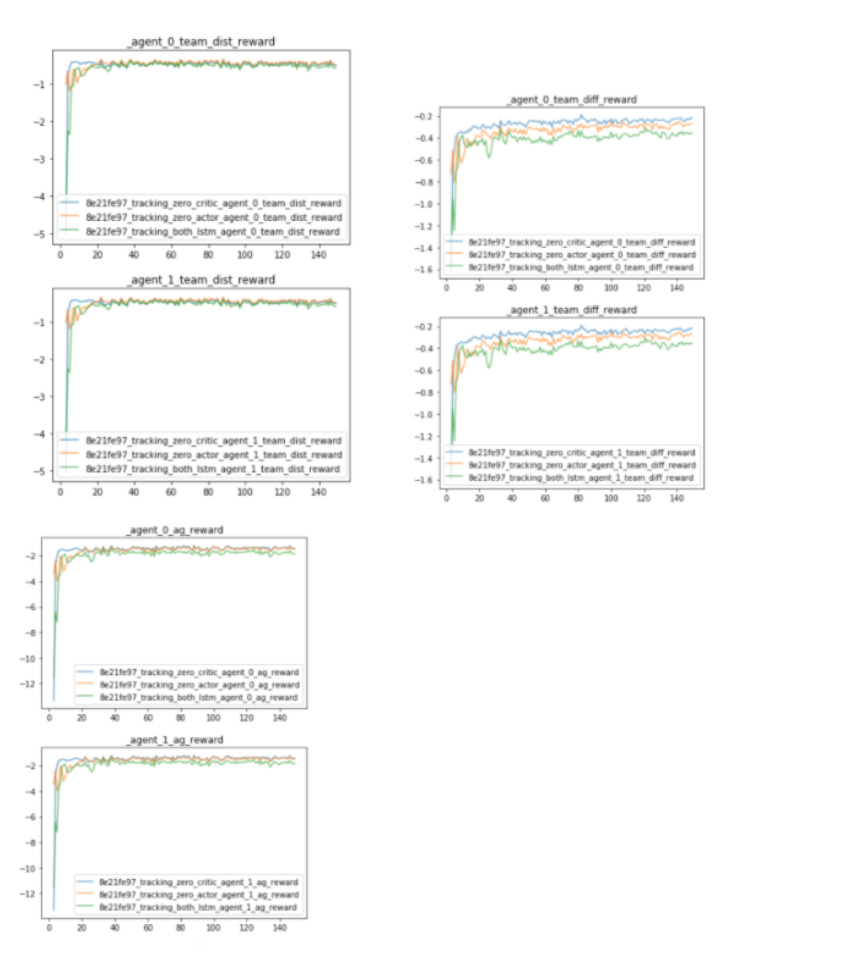

My research documentation is a tool I heavily relied on to create a sense of progress. Below, I draw a few examples of how I used my research documentation (a Google Doc) from the first machine learning research project I led during my junior year.

Use your documentation to engage with related works.

Because I lacked background in machine learning when I started my first research project, I read a lot of papers and got trapped into rabbit holes: I would pick up one paper, start reading it, get stuck on understanding the first or second paragraph, and end up with 10-20 more papers to read before I got back to the original paper I wanted to read. As a result, I felt overwhelmed with reading the literature.

It’s important to read with a purpose, not just for the sake of reading the paper. Your purpose for reading might change depending on the state of your project. For example, at the start of my project, I read in order to determine an interesting problem statement to work on. Later on, I read papers related to the problem I was working on in order to understand, compare, and contrast their contribution to mine. However, the lesson remains the same: Always try to read a paper in the attempts of tying it back to your project.

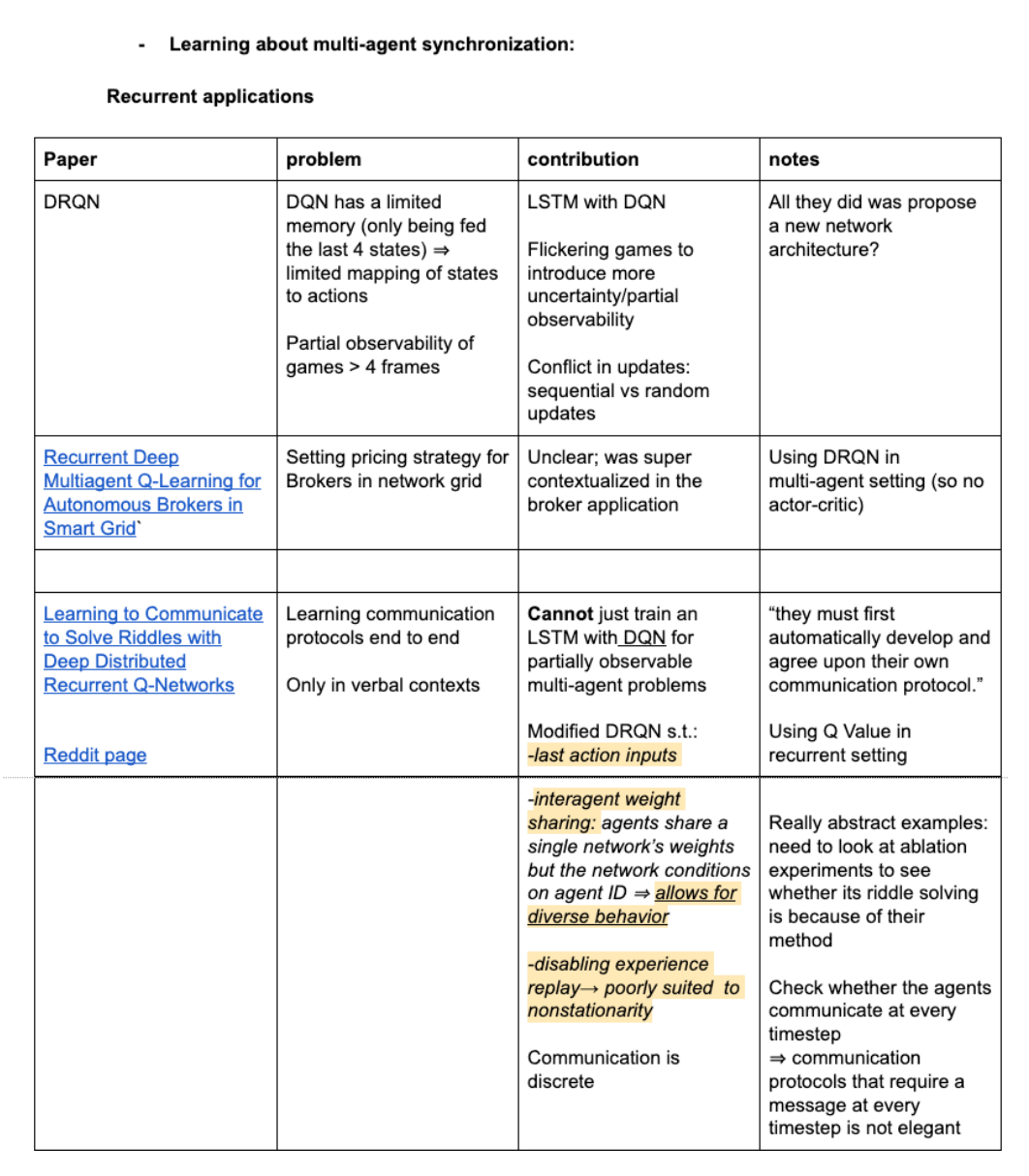

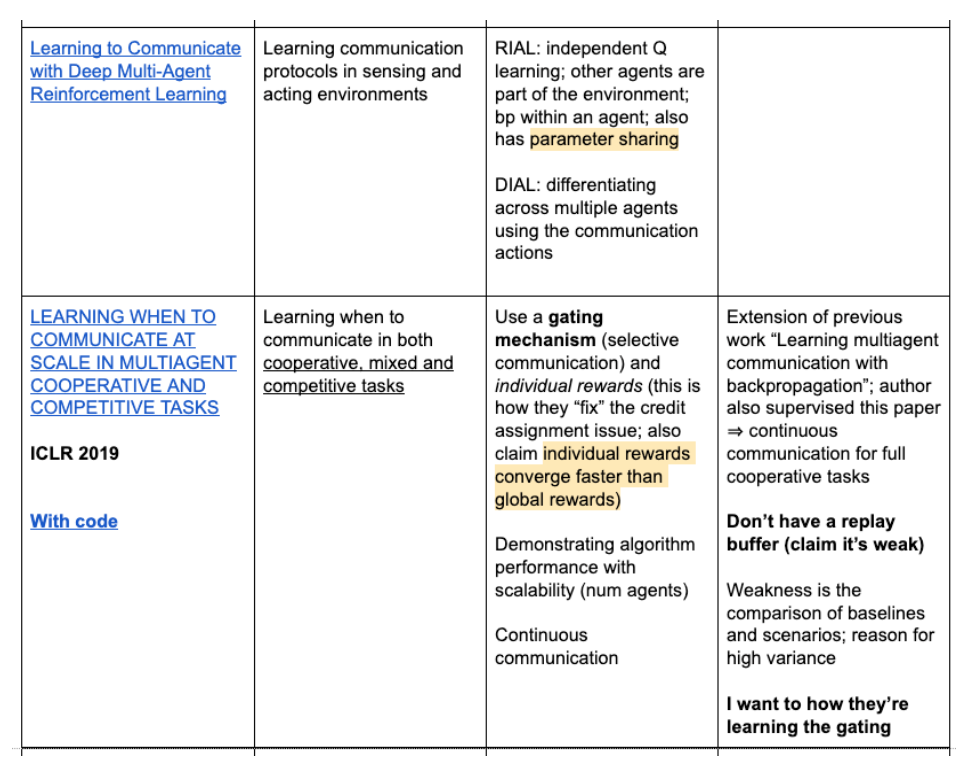

A simple way I achieved this is by documenting the problem and contribution of each paper, like shown below. For example, I created columns for the paper name, their problem statement and contribution.

The more I read, the more nuanced my purpose for reading became. Eventually, I also created a column for miscellaneous notes to answer questions like:

- Is this paper proposing an approach that makes sense? Does it make assumptions that I agree with, or disagree with?

- Is this work interesting to me, and if so, do they have their code open-sourced? Is their work related enough to mine for me to try out their code?

- Has somebody in my lab tried out the code for the work I’m interested in? What were their experiences like? What did they like and dislike about the work? Could I improve the work, and would that direction be exciting for me?

Use your documentation to plan your project milestones, week and day.

Research is different from your college classes in that it lacks structure, e.g. in the form of a syllabus. Thus, I found it important for myself to create a syllabus for research. A research syllabus guided me to use my time most effectively.

For example, a research syllabus could consist of your research milestones: What do you hope to contribute with your project? What questions do you need to answer in order to get to those contributions?

Your project milestones ultimately structure what you want to achieve in a given week: By the end of the week, what do you hope to show? With a plan for the week, you can better determine what you’d like to tackle on today.

Use your documentation to apply the scientific method.

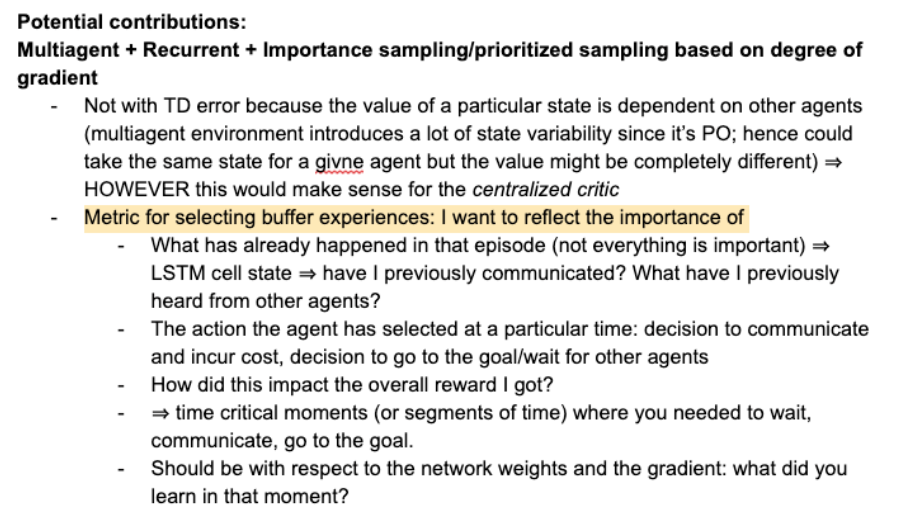

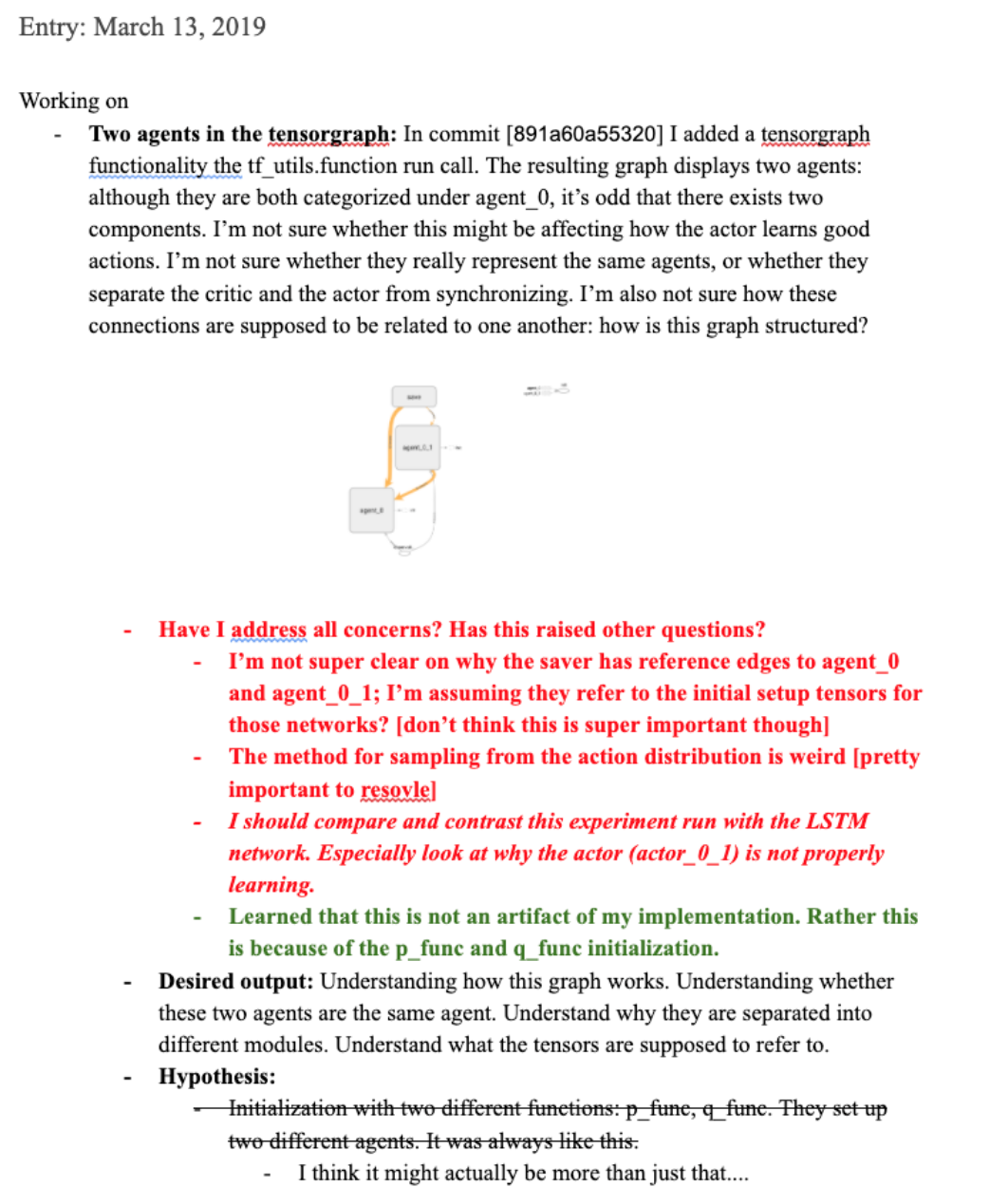

I was stuck on a bug in my first research project for four months. I wasted a lot of time inefficiently debugging because I experimented more than I thought about my experiments. It wasn’t until I read this blog post that I started to properly apply the scientific method to my research experiments and I escaped the long four months of the research slump. I spent more time thinking than experimenting. For every experiment I thought about doing, I filled out this template to ensure I conducted experiments relevant/useful in understanding my problem.

- (Description of the problem) What problem am I having?

- (Desired output) If I removed this problem, what should I actually be getting?

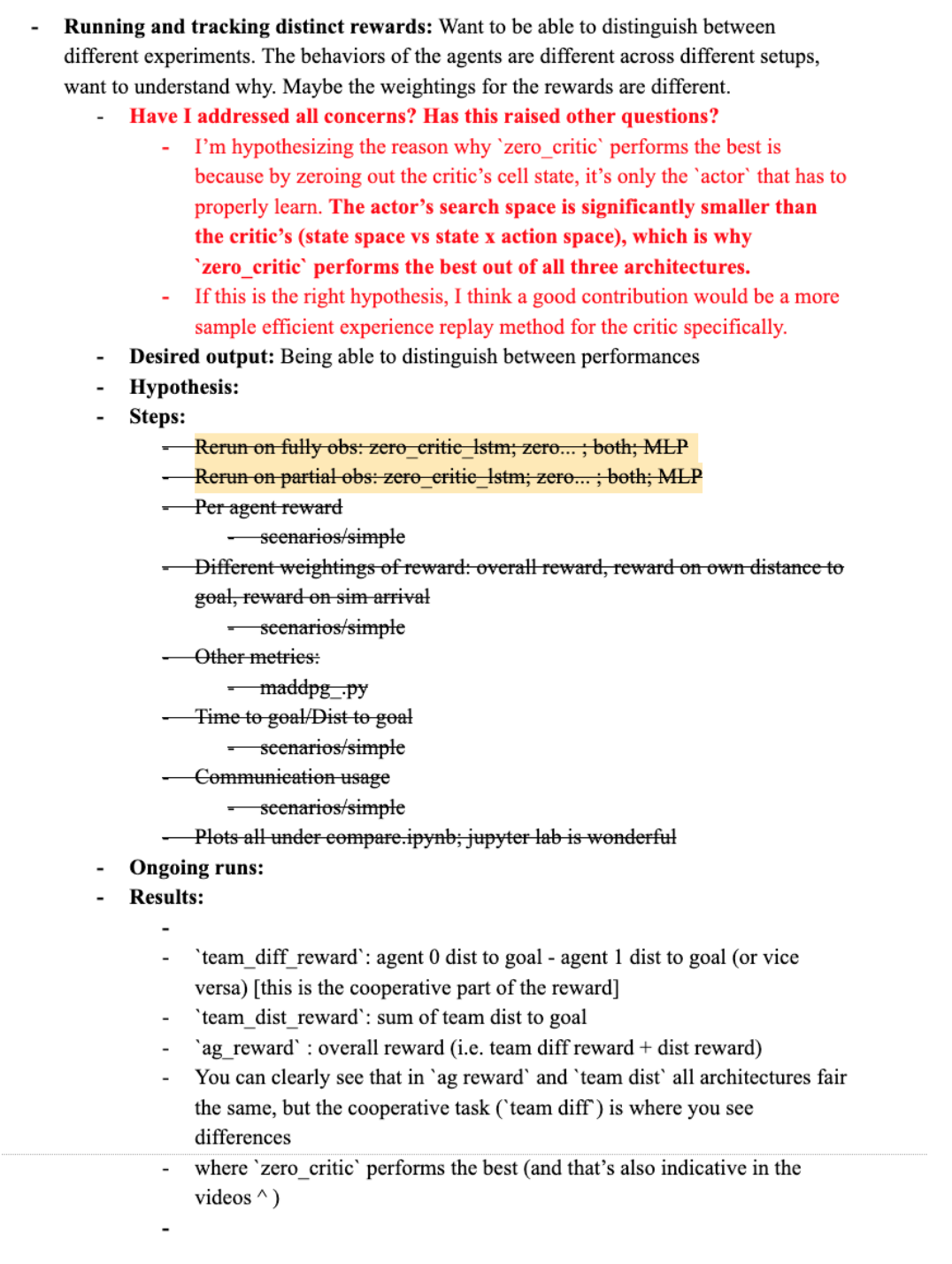

- (Hypothesis) Why is this problem occurring?

- (Steps) What should I do in order to prove the hypothesis is correct? What experiments would that need? What kind of infrastructure do I need?

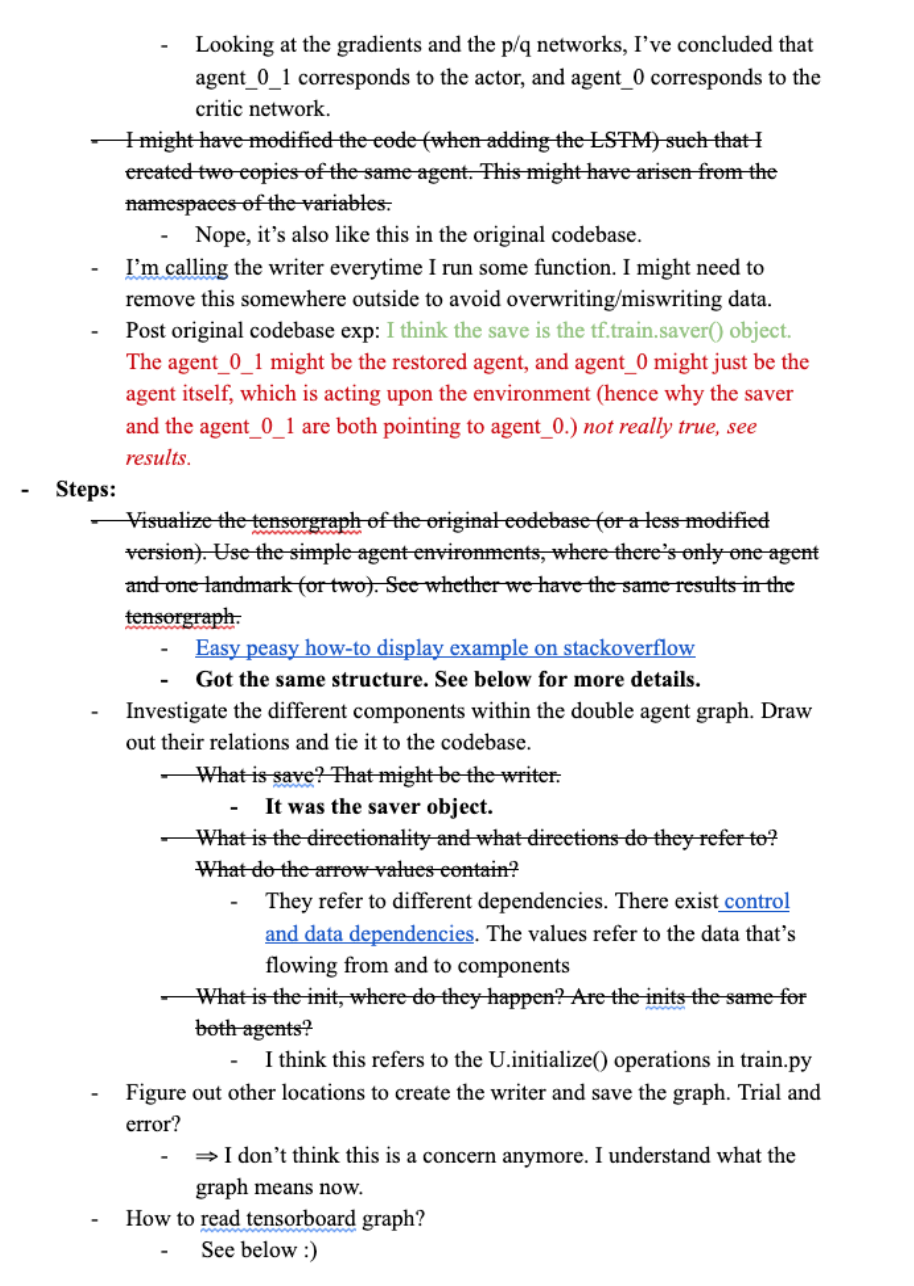

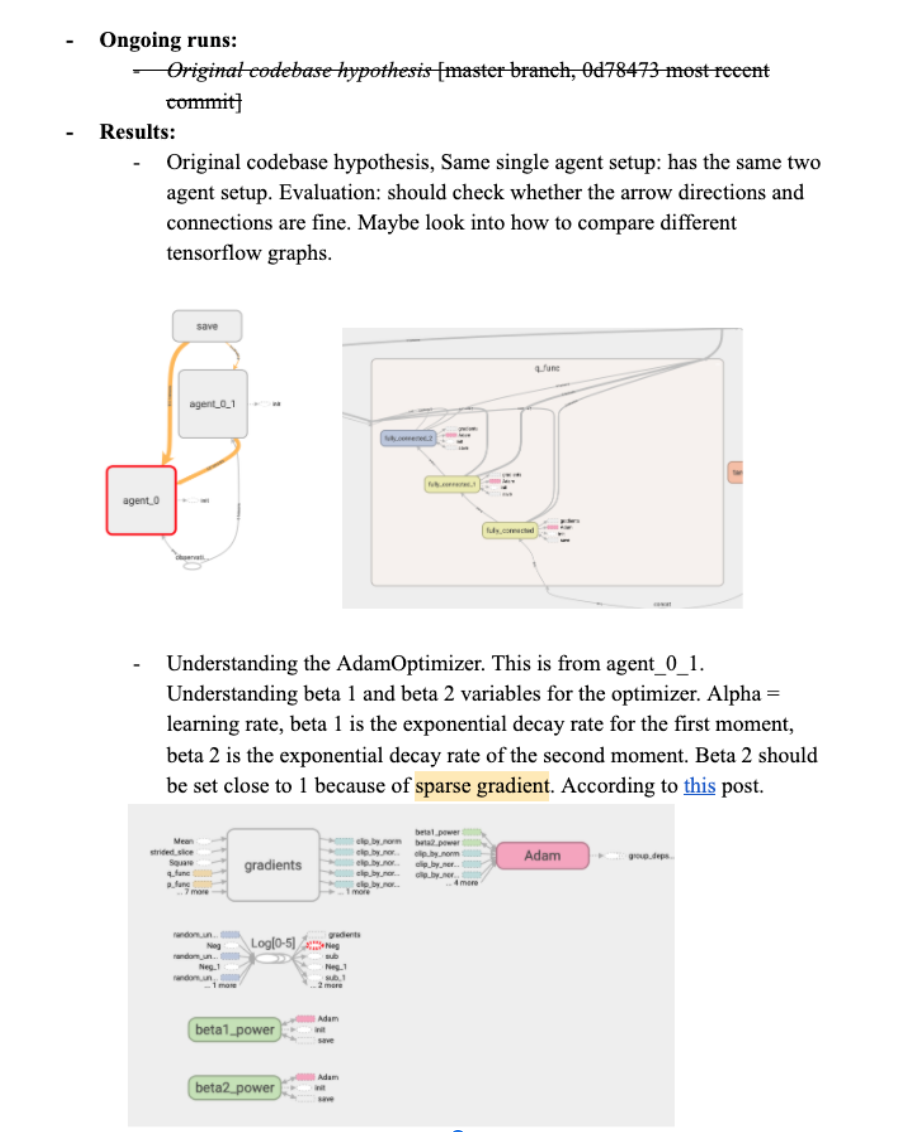

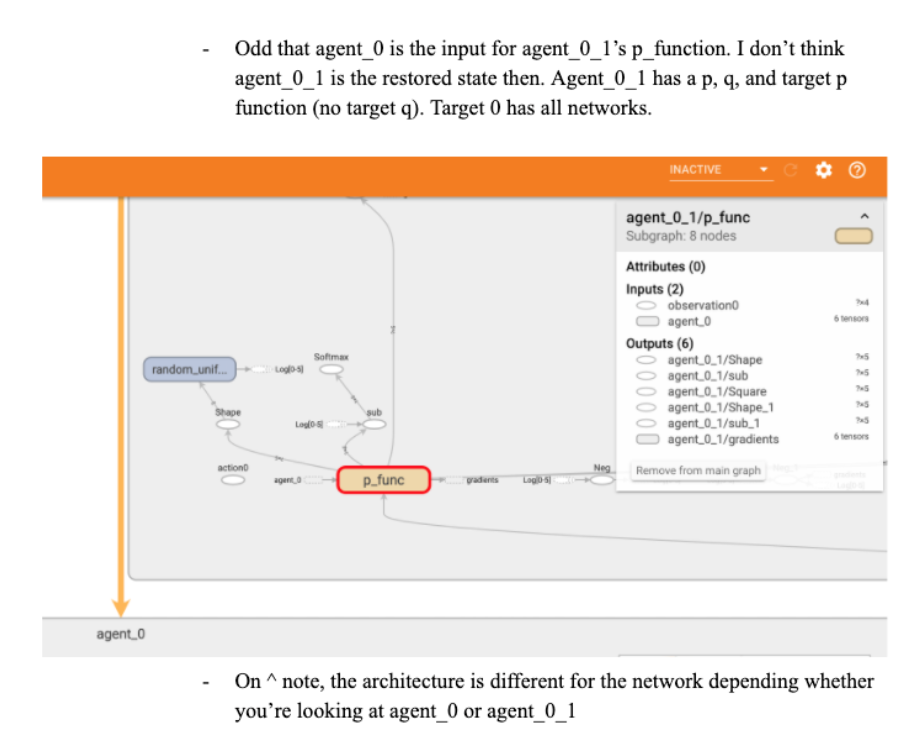

- (Ongoing runs) What experiments from “Steps” am I currently running? Here I could track the experiment id, the git commit hash code, or any other relevant information.

- (Results) What plots / screenshots / graphs can I show that either prove or disprove the original hypothesis?

- (Have I addressed all concerns?)

Reflection on C.

I really like documenting my work because

- It makes me think more, and experiment less. I think it’s important to be intentional with how we spend our time and I don’t feel happy when I’m running a bunch of experiments without properly thinking where each experiment is going to take me.

- I like to look back at the progress I’ve made. Seeing analyzed data makes me happy. :)

- I like talking to myself in writing. I like writing comments to myself in my documentation and I found it to be like a written form of rubber duck debugging.

An unplanned for side-effect of thinking more and experimenting less: I got into the habit of automatically logging and analyzing data—I was always thinking about how to prove/disprove a hypothesis in the form of a graph, figure, or plot. This is possibly one of the most useful habits you can develop as a researcher. Through the process of carefully understanding and breaking down your experiments, I felt like a proper scientist.

Problem D: Becoming more efficient at doing research.

I often thought about what tools/software/apps I could use in order to be more efficient at doing research. How can I better document my research? How can I become a faster coder? How can I write better plotting code?

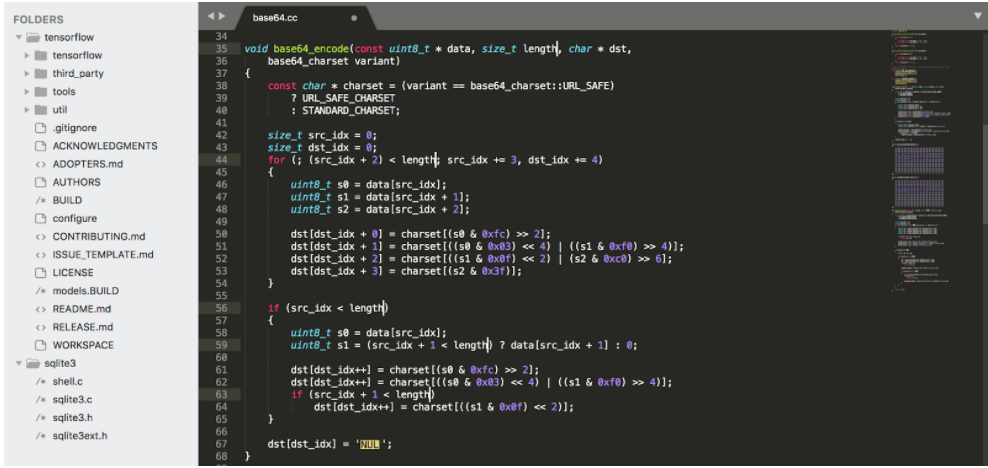

Approach D: By learning about other people’s tools.

The best way to learn how to do research is to learn from others around you, such as in a lab environment. How do they do research differently from you? What tools do they use?

For example, early junior year, I was sitting next to a friend who was using Vim to edit their code. I was amazed by how fluidly she coded and edited files all through her terminal. She hardly touched her mouse. By contrast, my coding process all happened on Sublime Text and I spent more time than I wanted navigating the file browser. This meant that when I had an idea for research, I would spend the first few minutes trying to click/find/open directories to the right files, before returning to implementing/testing my original idea. The speed at which my mind thought of ideas was often bottlenecked by my research tools. I asked my friend about her coding setup and the following week I tried out Vim; now, it’s what I used every day.

Reflection on D.

It’s small things, like acquiring a new tool, that can greatly improve your productivity as a researcher. Be proactive in acquiring these tools. It might end up being a matter of minutes of just asking/messaging/emailing other people about their tools which will end up saving you hours of work!

Problem E: Having better meetings.

When I started having regular meetings with my graduate student, I was initially uncertain about what I should talk about during the meetings. I also noticed that I had the tendency to ramble without a particular discussion goal in mind, which often led to awkward silences. I wanted to figure how to have better (e.g. more efficient and fun) meetings with my supervisor.

Approach E: By preparing for meetings.

I started to prepare ahead of meetings. I would make sure that I would have an outline of an agenda containing a mix of the following:

- Recap. What have I done since we last met? Be concrete. Do I have figures or images to show what I’ve done? What things surprised me?

- Questions. What am I stuck on? What do I not understand?

- Advice. What do I need help on? Who can I talk to about a particular issue I’m having?

- Next steps. What do I hope to accomplish in our next meeting? What milestones do I hope to reach?

I think it’s important to structure your agenda with empathy. What does that mean? Here’s how I like to frame it: You’re about to go into a 30/60-minute meeting and talk about things that you’ve been working on for the past days/weeks. Most likely, your supervisor might not have the right context to understand why you worked on a particular task. How would you go about the meeting now?

There are different mediums you might want to try for your meeting log. I’ve seen people use: Google slides (good for figures and keeping your summaries succinct), Google Docs (merging it with your general research doc), Overleaf (good for showing equations and formalizing paper ideas) and Notion (tracking your meetings in a Notion database).

Reflection on E.

I think I started this habit of preparing for meetings because I was scared of running out of things to say to my supervisor. I think there were a lot of positive side effects with doing this approach:

- Improving communication skills. I’ve found that figuring out how to best go about my agenda has improved the way I communicate my research to folks not a part of my project.

- A purpose for having good research documentation. I like to use my next meeting as motivation to have better research documentation, e.g. I’d think about what kind of graph/plot/video would help my supervisor understand my experiments, and in turn that also helps me create better documentation of my experiment results. Oftentimes, communicating your experiments in the form of an image/graph/video is a lot more powerful than reading aloud a long paragraph describing what you did/found.

Problem F: Finding your confidence/motivation to keep doing research.

During my first research project, I experienced 4 whole months of not making progress because I was stuck on a bug. What does that mean? It means spending a total of 120 days, going into the lab and staying there for two to five hours at a time and ending the day where I started it, during the cold, windy Boston winter season. I started to lose motivation for a project I was so excited to do because it was my own. I started to feel like I wasn’t good enough for research. I started to regret doing a more independent research project. I started to lose confidence in myself and the motivation to continue the project.

Approach F: By building and relying on your support network.

When I hit this low point in my research project, I waited for months before daring to reach out to my friends and talk about the problem I was having. I felt like reaching out made me a weak researcher because I wasn’t self-reliant — aren’t competent researchers supposed to be self-reliant?

Don’t let your personal source of happiness, confidence, and motivation be solely dependent on your research project. Make sure to build and reach out to your support network, even just to take a break from thinking about your research. For example, mine consisted of:

- My undergraduate friends who weren’t doing research. Over the weekends and sometimes after class, we went hiking with an outdoor club, ice-skating at our college ice rink, watched movies, went out to grab food, etc. We also organized tea parties on campus where we would reserve an empty classroom on campus, drink tea, and talk about big life topics.

- My undergraduate friends who were doing research. We ranted about things that weren’t working out for us and showed each other results that were working for us. We ordered/got food and sat together in an empty room to work on research together.

- Friends of friends. I really enjoy meeting new people so some of my friends would connect me with their friends. Usually, I’d grab lunch or coffee with them.

- My family, research labs, graduate friends, etc.

- Myself. I often reminded myself of my research dream. It’s a dream that is my source of personal validation. It is my reason for why I’m doing research!

Reflection on F.

I loved doing research during my undergraduate—unlike in classes, I had the freedom to learn and understand whatever I wanted in research. This is why I gladly poured hours into research. But, the success of a research project is not something I have complete control over. This is why it’s even more important to also find happiness in communities/activities not related to research.

I hope this letter helps you in your own research journey. Feel free to let me know if you have any other questions.

Warmly,

Rose